The Death Of Subculture part 4: the changing role of music and clothing

This is the fourth article in a series that aims to explore how subculture has changed in the last 30 years. To read part three click here. New to the series? Read part one here.

The role of music

Music is a particularly good way of literally and symbolically representing a lifestyle or viewpoint: the anarchy of punk, the cathartic brutality of heavy metal, the optimism of ecstasy-fuelled dance music. And the lyrics reinforce the message.

This perfect synergy meant that music often became the key tool for expressing oneself – expressing ideological values and subcultural messages. Part of the power of this synergy was that it allowed subcultures to become recognisable ‘brands’ to insiders and outsiders. People who broke these rules often found their message didn’t resonate with the faithful and confused outsiders. Christian hair metal, jazz metal, rap metal lots of white hip hop (until Eminem) and capitalist punk remain fringe experiments or simply don’t resonate with anyone.

Music with a message

The more pure the subcultural expression – complementary music and message – the more powerful. And so the faithful are usually keen to preserve the stylistic purity of the music.

While this is true, new subcultural needs meant new methods of expressing and subcultural shift and/or schism occur. The rate of change in musical style was invariably constrained by subcultural needs – progressing when new needs/applications arose. For example: London’s West Indian community mixing techno and hardcore of white Europe with funk and their native reggae to create jungle a uniquely British music for a second generation of immigrants who wanted their own sound.

If an individual has no particular message – or a personal message, not a group message – then they are free to use any musical style, or many musical styles. If no one has any particular message, then no one will align with any given scene, no one will follow any rules and the musical output of a generation becomes a chaotic, anarchic and un-navigable landscape. Without being tethered to subcultural rules, music can change at will, in any direction, at any speed, simply at the will of the creator.

Bowie was a rarity

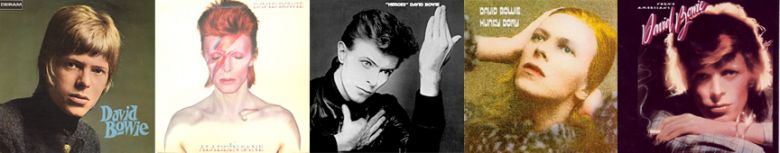

A great example of this is David Bowie: always the innovator, never following the crowd, exploring the unexplored. He outlived a dozen zeitgeist scenes from Mersey beat and psychedelia to the new romantics and jungle. He is notoriously hard to pigeonhole and the master of reinvention. He also has no subcultural affinity. Bowie was a rarity.

Today, many musical acts and teenagers wants to be like Bowie: no clear singular message or set of values delivered in by ever-changing musical styles.

“Young people today don’t identify with music in the same way teenagers from the 1940s to the 1990s did. Their main influence used to come from art and musical movements because those were the teenage forms of expression, but not anymore. Teenagers still listen to music – they go clubbing more than ever – but the music doesn’t play the same roll in their lives as it used to in ours [the late 1980s]. That role has been filled be video games, social media, film franchises.”

Jon Lilley

NB: Head to the first article to read about our panel.

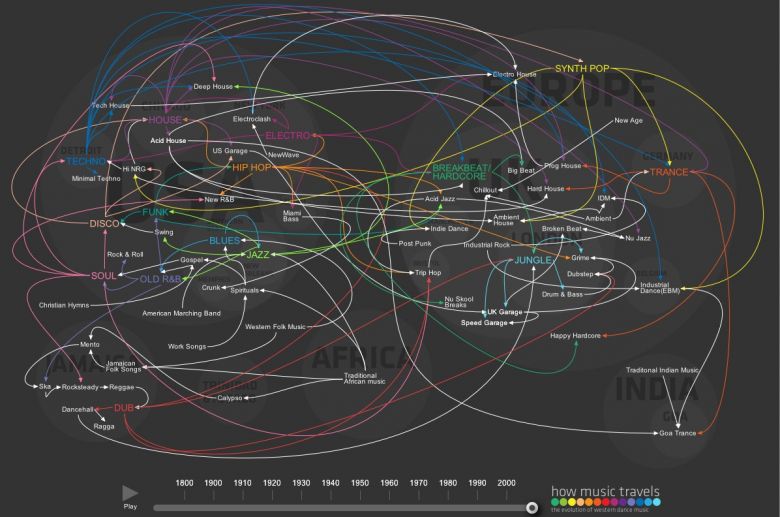

It could be postulated that this is exacerbated by the increasing individualism of Western society, the importance of unique. Since the 1950s, subcultures have divided like cells, driven by the increasing need to identify yourself more specifically as ‘different’ from others – even those who are most like you. The result of 70 years of fragmentation and combination is an almost infinite array of subgenres: progressive house, deep house, Italo house, trance, Chicago House, tech house, hard house, handbag house, hardbag, acid house, ambient house, funky house, French house, Electro (house), jazzy house, minimal tech, soulful house.

A representation of the dance music subgenre universe by MusicIsMySanctuary.com

Would it be accurate to say that while the traditional protest/message songs from 1960-90s were about social justice, the last 20 years has seen the growth of personal justice songs? ‘Let me be me’, ‘I’m beautiful no matter what I am’, ‘I’m authentic’.

Insider view: the role of the album

“My take on the whole subcultures thing is a bit simpler: Youth subcultures were all entirely music-driven. Those who came of age before 2000 could probably only afford to buy one album a month at most. You couldn’t afford to listen to or be into everything, so you had to pick a tribe. That album you bought had far greater weight, value and meaning to the individual than a playlist does today. With streaming and downloads, the album stopped being the primary unit of consumption of music and you could pick and choose whatever you wanted to listen to. Now you can listen to trap one minute and power metal the next. The result is feeling less like there is something you have to be loyal to.”

Amy Nicholson

Post-modern music

Music always evolves: it looks back for inspiration, then it leaps forwards with technology – from electronic amplification to synthesizers. It refines and focuses, then it looks to other scenes and countries for its path forward. This usually happens unconsciously, musicians just doing what they like because they want to (though I acknowledge that this may well be driven subconsciously by exterior forces, including subculture/culture).

Puritan, elitist and rule-based approaches to music were eroded throughout the late 20th century

Puritan, elitist and rule-based approaches to music were eroded throughout the late 20th century – often feeding or feeding off subcultures.

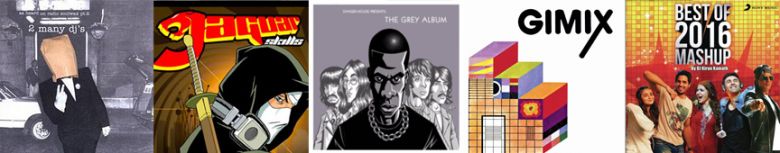

Cover versions had the power to make us hear the familiar in the alien. The remixing of the 1980s onwards accelerated this and allowed musicians (and labels) to recreate music in different styles for different audiences. This happened concurrently with sampling culture which saw parts of songs lifted from their original context and given new meaning in a new form in a new song. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, this gave birth to the very post-modern ‘bootleg’ or ‘mash-up’ music: musicians (including DJs) – such as Too Many DJs, The Avalanches and Jaguar Skills – would take two or more different songs and splice them together to create a ‘new’ track. Artists very consciously spliced ever more incongruous styles to get more and more surprising results.

Soulwax’s seminal 2 Many DJs mixtape/abum, Jaguar Skills, The Grey Album (mashing up Jay Z’s Black Album and The Beatles’ White Album), The Avalanches’ underground Gimix mixtape and a mashup album I found in Google – an example of how quick the mainstream is to adopt underground styles.

The subtext of this is that there are no rules governing what is acceptable to use or create, regardless of its original semiotic value. 1980s pop, hip-hop, thrash metal, punk, house and even novelty records become separated from their original meanings and collide something that carries none of the original meaning in this new and disassociated context. The musicians were consciously thumbing their nose at the ‘arbiters of cool’ by making something ‘great’ out of one or more things that weren’t.

Anyone growing up after 1980 will have done so to a soundtrack of co-opted and reappropriated music

Most generations react against the rules of their predecessors, but this new rule meant there were no rules.

Fans

This discussion is mainly about the creators of music and subculture. So, what about the fans? The followers? The niche herd?

Just as people’s needs to express something specific may have waned, so too has the need to hear a message in a certain way. This has driven music and scene promiscuity, which in turn has been facilitated by the internet. With an urge to ‘discover the next big thing’, no subcultural anchor (rules) and free access to a vast array of new things to explore, music becomes an unending journey not a destination; it is simply consumed and passed, not carefully selected and savoured. This could again be exacerbated by free downloading, which made recorded music literally valueless – the gig and the t-shirt becoming an act’s ‘products’.

This flyer for a club night is just opposite the office. To anyone over 30, this might seem too broad a church to keep anyone happy… anyone who is particularly into one or two types of music. That’s not odd: in the 1990s, there were lots of people who liked lots of different music, but it tended not to be underground/niche music like UK Funky or Dancehall.

Another argument is not that people have less to say, but that individuals have other, cheaper, easier, more immediate avenues for doing so:

“Music is no longer the vanguard it once was. It’s being replaced by forms that are even more immediate, mostly social media. Nowadays, people post online what they might once have put into a song. Similarly, the information people once got from, say, The Clash or Public Enemy, they would get from a blog today.

Ian Winwood

Nowadays, people post online what they might once have put into a song

“The software side of technology – programmes such as Logic – used to write and produce music, has enabled many more musicians to get their material to a releasable level for a fraction of the cost it would have done 30 years ago. Not only are more people creating music, but from MySpace onwards artists didn’t need a record label to release material – you could directly access an audience.

“However, due to the internet, audiences have a much shorter attention span these days. If the band they love take time off to record or have a break, the scene has often moved on and their fanbase is lost in a short amount of time. But a band cannot continuously be in campaign, or constantly be on the road without eventually imploding.

“The movie industry tackled file sharing and copyright infringement quite well, but, especially in the early days of the web, the music industry was slow to develop a business model and make sure artists still retained a decent enough income stream to survive.

“Physical product doesn’t shift in nearly the quantity it once did and even albums don’t sell like they used to – it’s all singles and EPs. Artists make far less from a download or a stream, so it’s much harder to survive. This, in turn, means that subcultures may not have time to emerge or last as long when the driving force behind them quits.

“When I was a touring musician [in the 2000s,] if you wanted to check a band out early on in their career, you had to go to their gig. Now everything about them is accessible online: live footage of shows, their catalogue etc. This also has a consequence for venues, with many iconic bars and clubs closing in recent years.”

Ross Gidney

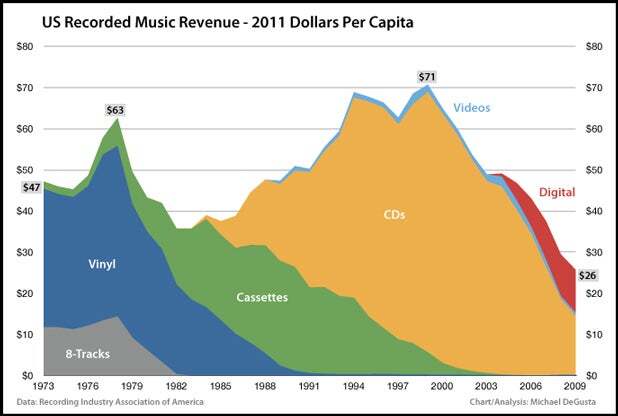

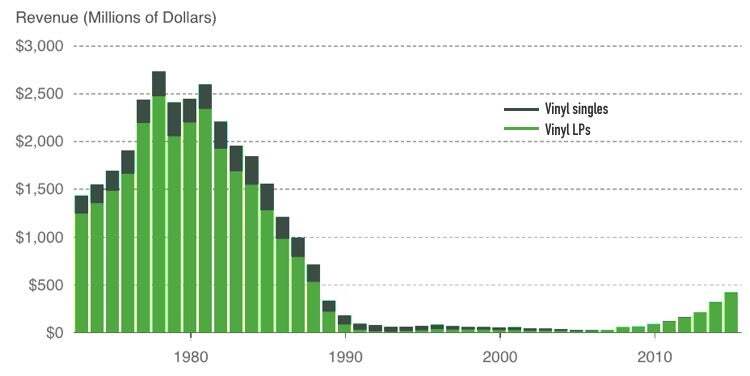

NB: I’m often told how vinyl sales are up. Here’s what the ‘vinyl revival’ really looks like:

Mad Men [the US drama set in a 1960s ad agency in NY] addresses the power of music directly: in the 1960s, brands became aware that certain (youth) audiences would respond to certain music – and therefore, any product associated with the music. By aligning music and product in radio and TV advertising, brands could more effectively sell to these audiences.

The role of clothing

While music can have a literal and symbolic power to communicate the message of a subculture, it usually communication within the scene – for the scene. Clothing is arguably more powerful as messages can be more instant and we can take our messages to the public more easily than via music. While not all members of a scene can create music, most will be able to dress according to the rules of the group and take the message wherever they go. While punks had a socio-political message, most scene members just want to say:

- I’m this

- I’m not like you

As well as the overt messages of ‘I’m not like you’ it is a way of identifying ‘friends’ in strangers.

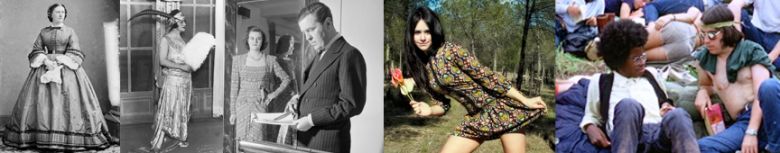

L to R: Victorians raised the young adults of the 1920 and 30s – many of those who could, distanced themselves from strict parents by their dress and activities. Post-war children (right) did the same, purposefully dressing differently from their parents (middle).

The hippies used clothing to show how different they felt from their parents generation. Today, it is not rare for 45-year-olds to dress similarly to their children: jeans and t-shirts from Primark or Topshop. This could be less to do with ‘parents dressing like their kids’ and more to do with ‘kids have no desire/need to dress differently from their parents’.

It doesn’t take a quantitative study to know that there are fewer identifiable subcultures on our high streets than in previous decades: gone are the punks, the goths, the emos, the ravers, the rockers and the hippies.

‘David Bowie Syndrome’

David Bowie’s career spans six decades – starting in the late 1960s and continuing through until his death.

Bowie’s look, music, values and messages seemed unrelated to the zeitgeist of the times through which he travelled. Despite releasing albums since 1967, Bowie never released a rock album, a punk album, a disco album, a dance album or a metal album though some of his songs borrowed from these influences. Bowie’s look and music kept changing – he was the master of reinvention, and reanimation.

His looks and music were synthesized conceptual constructs, not simply a facsimile or interpretation of the zeitgeist with a best before date.

This is what made Bowie one of a very small number of acts who were able to sustain popular and cult appeal without ever being a part of the dominant subculture. If you are tied to a ship, you will sink with it.

Now, everyone is like David Bowie. From the bands to the fans.

With unbridled access to a universe of cultural reference points and, in some cases, technology, combined with no singular subcultural driving force, there is almost infinite scope for self-expression.

With no subcultural centres of gravity, everyone floats about in the vacuum, all unique, equally different, all in a subculture of the self.

The purpose of subculture has shifted from saying, ‘we’re not the establishment’, through ‘we’re not like the others to ‘I’m not like anyone else – I’m just me’.

Once you start examining subcultures online, things become blurred and confusing, compounded by the fact that a lot of online subcultures seem to come cloaked in layers of irony

As Alexis Petridis writes:

“Once you start examining subcultures online, things become blurred and confusing, compounded by the fact that a lot of online subcultures seem to come cloaked in layers of irony… I can’t work out whether what I’m looking at is meant to be serious or a joke… There’s plenty of stuff that seems weird and striking and creative out there, but there’s something oddly self-conscious and non-committal about it.”

Sounds a bit like Bowie.

“The youth of today are different to the youth of previous generations in one fundamental way: we wanted to belong. Young people today are still tribal, but they want to stand out as individuals too. They are aware of their own identities and are less keen to be actively seen as part of a subculture. In the 1970s/80s we would proudly state ‘I am a Mod’ or ‘I am a Rocker’. We would look to be one of that crowd – that doesn’t happen now and I think that has had a big effect on appearance-based subcultures.”

Jon Lilley

Click here to read the next installment of The Death Of Subculture. Part Five: The Role of Media And The Internet.

.png)

.jpeg)